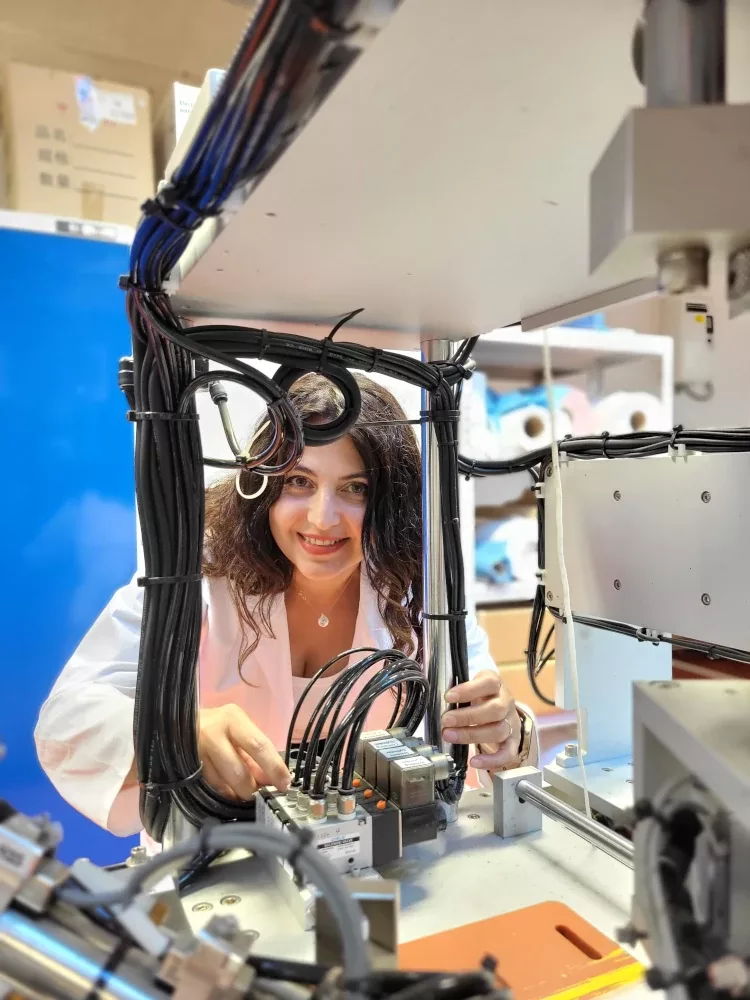

"It amuses me when people tell me they don't believe in nano," says Fatma Yalcinkaya

"It amuses me when people tell me they don't believe in nano," says Fatma Yalcinkaya

Trójstyk / Dreiländereck / Trojzemí

»Nano in environmental protection. What does Fatma Yalcinkaya do?«

She has discovered new ways to use nanofibers in the environmental field. Fatma Yalcinkaya is a scientist whose name resonates both here and abroad. More than a decade ago, it was the nanoscale world that attracted her to the Technical University of Liberec from Turkey.

Fatma comes to our interview right on time, ready for every question. It is clear at first glance that she has a fixed direction she wants to take, but she comes across as very modest and pleasant. Her dedication and diligence is paying off, as she has been among the top 2% of the most cited scientists in the world for four consecutive years across all fields covered by Scopus, according to Elsevier and SciTech Strategies together with Stanford University.

Nano-small, mega-interesting

Fatma chose the textile industry in Turkey because it was at a high level at that time. She chose the Technical University of Liberec as her Erasmus traineeship. Here she fell under the spell of the nanoworld. "The nanoworld is really small, but also really interesting. I like that it is a multidisciplinary combination of chemistry, polymers, materials or physics. I chose Liberec because it is one of the world leaders in nanotechnology," she says.

At TUL she met Oldřich Jirsák, who made the first industrial nanospider. And she was rightly impressed. A nanospider can really be imagined as a spider that forms filaments so thin that a microscope is needed to see them nicely. But this device works much faster and is slightly larger than a human. And it is in speed that the nanospider is groundbreaking.

Partners also in research

In 2010 she decided to move to Liberec permanently and took her husband, who also worked at TUL but now works for the company, with her. She and her husband are also partners in research and help each other out. "He is a support for me, even though he accidentally electroshocked me once," she laughs. "After a grueling day of taking measurements for my dissertation, I still had my fingers on the needle where the fibers are forming. There's a voltage attached to it. And my husband didn't notice and accidentally let electricity into me. It wasn't explicitly painful, but it was unpleasant," Fatma recalls.

Contact between research and industry

Before Fatma joined the Institute for Nanomaterials, Advanced Technologies and Innovations at TUL, she tried her hand at working in a research company partly supported by the state, which focused more on basic research. "There was high-end instrumentation, we were given training on the different instruments and could use them. There was also a unique opportunity to publish much more frequently in the top decile. On the other hand, there was also a lot of competition and the pressure was discouraging. At TUL it is different, we can only work on instruments within our department. If we want to use another instrument, we have to find a project that will fund the work on it. But the facilities here are great," explains Fatma, for whom the positive side of CXI TUL is that the people there are very nice and there is a close connection with industry. She sees her research being used in industry.

"I never imagined the direction I wanted to take. I wanted to travel the world and explore. And as a scientist, that's exactly what I'm doing. I really enjoy it, meeting new people or new directions in research. Working at a university gives me more opportunities to start new research. In industry, I am closer to the real application, but starting new research is not so easy," Fatma lists the reasons why she chose a career as a scientist at university.

Who doesn't believe in nano?

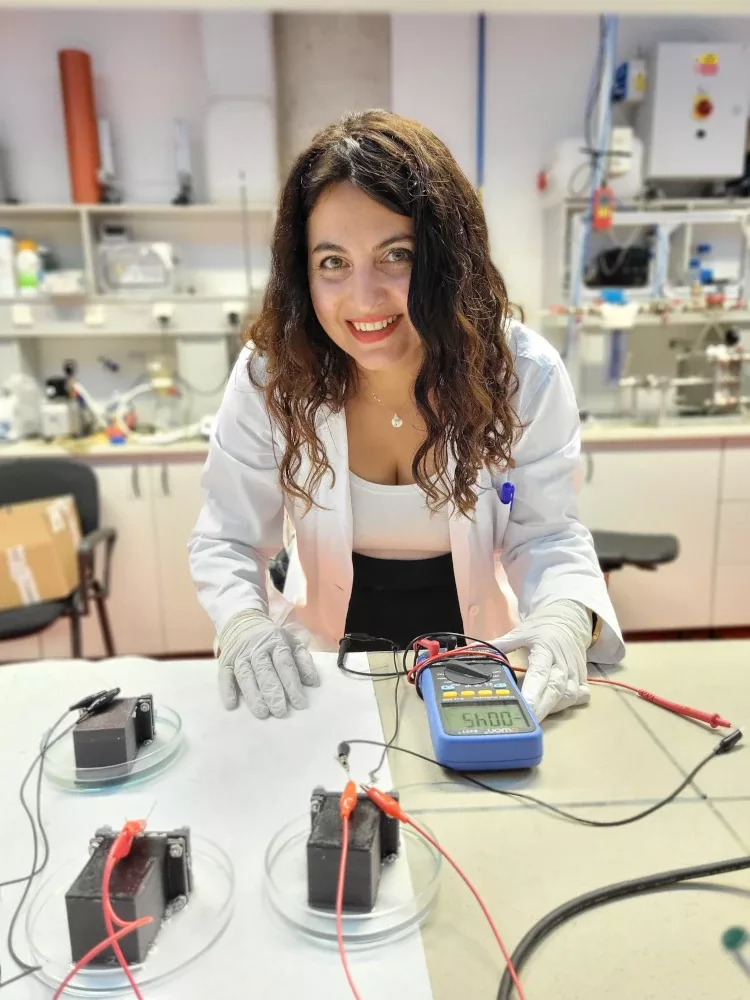

Pure joy. That is what I feel from Fatma as soon as she starts describing her research on microbial fuel cells. Such a cell is made up of microorganisms from wastewater, and the wastewater also serves as a source of organic matter that is their food. The bacteria convert the food into electrons and the energy in them is further used. "Microbial fuel cells don't just stay in the lab. The system has been used to power a Glastonbury Festival or is being used in Africa as a light source in public toilets by top one of the top scientist Prof. Ioannis Ieropoulos and his team in UK."

"I'm always surprised when someone says they don't believe in nano," Fatma continues to explain her research with amusement. "And yet it has so many different applications. For example, I work on membrane technologies for water purification and reuse. I prepare the membranes myself using nanofibres and they can trap a spesific range spectrum of substances, even microplastics or oily substances. But such a membrane can also be used for water desalination as support layer or air filtration," she enthuses, explaining the future directions of her research.

Under the hood of companies

Fatma is currently working most intensively on a project funded by the international Visegrad Fund, which connects the Technical University of Liberec with academic institutions in Poland and Hungary, as well as with industrial companies. "Our goal is to create a network of excellence in the field of nanofibers in the V4 countries involving three respected academic institutions and industrial partners. So I am bringing my knowledge about nanomembranes there. It's a project more focused on sharing experiences, but because we are also working with companies, we know which problems are burning the industry and what else we have to work on. I think if the science stays behind closed doors, there's no point. I'm very much in favour of open science, open science facilitates the exchange of knowledge and contributes to the development of science internationally. At the moment I am busy preparing the workshop," Fatma concludes.

Czech family

And where does Fatma see herself in five years? Again at CXI TUL. She is simply happy here, perhaps because she received a really warm welcome at the beginning. Her thesis advisor picked her up at the airport and brought her to the room she was to share with her roommate. He helped her with her luggage and prepared a few essentials for the kitchen so that she could prepare a meal. "My roommate thought he was my dad. And indeed, in reality, my dissertation advisor and his wife became my Czech family. I really appreciate their help."